This article was originally a CRM survey report that was popularized and published in True West magazine, Vol. 40, No.2, February 1993. © 2014 by the author.

THE CAJALCO DIGS:

Exploring an Early California Mining Camp

by

T.A. Freeman

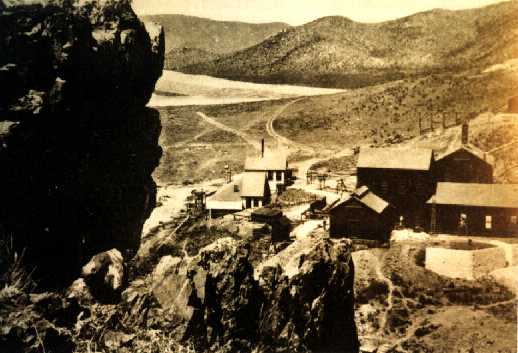

Smelter and reduction works of the Cajalco Tin Mine in 1891

(photo: Title Insurance and Trust Co., Los Angeles).

The down side of conducting an archaeological survey on land scheduled for development is that 90% of the time you find nothing of interest. I have often spent days (even weeks) transecting on foot parcels of thousands of acres, looking for that one unreported and elusive prehistoric Indian site or some historic feature worth recording for posterity. More often than not, the field reconnaissance end of cultural resource management serves only to flush a few rabbits. Occasionally, however, the odds pay off and make the drudgery of search pale in contrast to the thrill of discovery.

Those of you who are familiar with USGS topographic maps know that sometimes the landmarks shown don’t exist. Time and man often obliterate distinct geologic features, and buildings that may have once stood are razed to make way for parking lots or housing. In the case of my particular survey near the Lake Mathews area of western Riverside County, the maps indicated the presence of an old mining site known as the Cajalco Tin Mine (pronounced Ka-hal-ko). Basing my conclusion on previous experience, I had little hope of finding anything more than tailings.

Photo: Present-day view of the mine taken from the same location as the 1891 photo.

Although the structures that once stood had been removed long ago, I was amazed to find several rock and concrete foundations of various sizes scattered over an area of perhaps ten acres. Palm trees, junipers, and willows had been planted around the mining camp, and there was even an olive orchard. Additionally, several of the mine’s vertical shafts were still open, extending to dangerous depths of over 100 feet. At first glance the extent of the camp and its facilities suggested that the Cajalco Tin Mine was, at one time, a very large and profitable operation.

Some armchair research revealed that the Cajalco Tin Mine had also been referred to as the Temescal Tin Deposit. Temescal Canyon, approximately two-miles west of the site, was once part of a 50,000 acres Spanish land grant known as Rancho El Sobrante de San Jacinto. Originally, this immense tract of rugged, mountainous terrain fell under the jurisdiction of the mission San Luis Rey de Francia between 1798 and 1832. Because it forms a natural passageway through the mountains, the Temescal Valley had served as an old Indian camping ground, later becoming an alternate route of the Southern Emigrant Trail in the 1850s and 1860s, as well as a Butterfield-Overland stage corridor.

Photo: View of a partially subterranean rock and concrete foundation. The walls of this structure are over a foot thick, with angle iron door supports and heavy iron hinges. Its construction suggests that it may have served as an explosives storage facility.

In regard to the unusual name of “Cajalco,” the story goes that Salano, chief of the Gabrieleño band of mission Indians and uncle to Daniel Sexton’s wife, was on his deathbed in San Gabriel and feared that the place with Indian “medicine” would be lost. Thus, he ordered his medicine man to show Sexton the sacred site. Soon after seeing it, Sexton concluded that the medicine in question was actually valuable “metaliferous rock.” Sexton began to mine the deposit which through him became known as Cajalco Hill--a hispanicized Indian name of unknown meaning. No claim has yet been found for Sexton’s original claim, but records show that he retained full ownership until June 28, 1859, when he sold half of his interest to one Nathan Tuck.

The news of Sexton’s discovery spread far and wide and spurred an unprecedented onrush of miners. Because nearly all of the ensuing claims were staked in the Temescal area, all were immediately referred to as the Temescal Tin Mines. Hundreds of claims were filed, some miners staking as many as a hundred a piece. It also quickly became evident that more money was being generated through the buying and selling of claims than what the mines actually produced. For example, records indicate that as late as 1868 one George Aiken has sold half interest in 170 “tin” mines for $15,000. It seems that such sales were not uncommon even though there was little, if any, profitable production.

The Temescal tin frenzy went unabated even after Professor Josiah Whitney and William H. Brewer, both competent geologists, visited the digs in 1861. Whitney’s impression was that the mines were located on streaks of common hornblende, and that although many samples had been taken, not one trace of tin could be found. Disregarding such unfavorable reports, companies that had been solely formed to exploit the potential tin bearing lands in the Temescal Valley continued to sell and resell their interests.

Miners from as far away as Los Angeles and Orange counties tried recovering the elusive mineral with some limited success. The first major attempt at mining the Cajalco deposit was vertical exploratory shaft sunk 95-feet into the hard granodiorites. But the outbreak of the Civil War, coupled with a long and bitter litigation between claimants of Rancho Sobrante, suspended explorations for a time. Then on January 2, 1868, mining was officially resumed with the establishment of the San Jacinto Tin Mining Company which purchased Rancho Sobrante and the Cajalco. Interestingly, Whitney’s initial conclusions were proven incorrect. That same year saw the first shipment of 15.34 tone of cassiterite ore to San Francisco, which, when smelted, yielded 6,895 pound of tin.

Such was the hope of the Cajalco’s success that bars of tin from the mine were exhibited at the Mechanic’s Fair in San Francisco in 1869. Ore specimens were sent to England where they were pronounced the purest in quality. Investigators of the time stated, “Here was a body of tin, unlimited in quantity and of the finest quality--the richest and only workable body of tin in America.” English experts examined the region repeatedly and finally two English companies with considerable backing incorporated with the intent to purchase and exploit the deposit.

In 1890 the newly-formed English syndicate officially acquired the Cajalco, erected a smelter, and began to seriously work the veins. Production was increased many times with the help of two “Husbands” pneumatic stampers which weighed 900 pounds each and dropped at a rate of 135 times per minute.

In a January 1, 1891 promotional pamphlet asserting the virtues of nearby Perris Valley, it was noted that the English Company: “...had a force of one-hundred men improving the mines, erecting buildings, and constructing a large dam. Reduction works are being erected and two-hundred experienced Cornish miners will arrive in the spring when active mining will commence.”

What were claimed to be great pigs of pure tin were hauled to the South Riverside railway station (what is now Corona) and stacked into the shape of a huge pyramid. There, President Benjamin Harrison and California Governor Henry H. Markham honored the town by stopping and having their picture taken at the base of the pyramid. Atop this geometric mountain was an inscription proclaiming that this was the first tin produced in the United States.

By 1892 the company had invested well over 2 million dollars in the development of the Cajalco, a tide sum for that era. Yet even so, within the short span of two years, unwise investments and bad management led to the Cajalco’s abrupt closure. The expensive facilities were dismantled and sold at auction, and the for the next 35 years the Cajalco deposit lay dormant.

The advent of the 20th Century with its burgeoning industrialization brought new machines, technologies, and investors into the mining market. Evidently the American Tin Corporation, headed by P.H. Gorman and G.H. Bryant of Riverside, decided that the Cajalco’s full potential had not been played out and that it was time to re-open the digs using more modern recovery techniques. So, in 1927 the mine was reactivated and for three years extensive improvements were made.

Unfortunately, disaster stuck the nation’s economy with the fall of the stock market in 1929, and Gorman and Bryant were forced to close down the Cajalco once again. In 1942 the Tinco Corporation of Richmond, Virginia, revived the mine in order to supply the demand of the military effort of World War II. Tinco’s improvements included the installation of a 100-ton mill which operated until the Cajalco’s final closure in 1945.

According to historic documents, the Cajalco Tin Mine was followed to a depth of 690 feet without bottoming, and was explored with over 5,800 feet of drifts and crosscuts on seven levels. All told, the entire state of California had yielded less than 150 tons of tin by 1945. Of that, the Cajalco Mine was responsible for around 113 long tons and was the only tin producing mine in Riverside County. Ironically, continuing local hopes of establishing a viable tin mine were permanently dashed on May 25, 1953 when the Los Angeles Times reported, “The U.S. Department of the Interior said there isn’t any tin to speak of in the Temescal area.”

Photo: End of the line for this old Underwood found at the dump site.

Besides a wealth of history and the remnants of building foundations, we found other physical evidence of the mine’s early use. During our field reconnaissance we discovered square nails, horse shoes, and various other items scattered about. A dumping area just south of the mine yielded old cans and bottles dating to the turn of the century. But our most spectacular find was a silver coin found on the surface. Minted in Prussia and honoring Friedrich Wilhelm III, the coin’s date is 1828. A “D” mintmark on the coin indicates that it was probably struck in Aurich, East Friesland, Prussia--the kingdom that in 1918 fell and was absorbed by Germany.

Photos: Heads and tails of the 1828 Prussian coin found on the surface at the

Cajalco Tin Mine. The size is roughly that of a U.S quarter.

Although the true story behind the 167-year-old coin’s presence at the mine will never be known for certain, several plausible scenarios might explain how it came to be at Cajalco. One might be that it was lost by an early miner/emigrant traveling along the Temescal Trail. Or the English investors who owned the mine in later years might have hired a consulting geologist from Germany who lost the keepsake during prospecting activities. Or perhaps, because U.S. currency was in short supply during California’s early years, miners working at the Cajalco might have been paid with whatever moneys were available.

Ultimately, and regardless of its true origin, the lone Prussian coin stands as a unique testament to the colorful history of one of Southern California's earliest mines.

Bibliography

Freeman, T.A., and D.M. Van Horn

1989 Archaeological Survey Report: Cultural Resource Assessment of 800 Acres in the Lake Mathews Area of Western Riverside County, California (Ultrasystems Job No. 4520). Unpublished report on file with Archaeological Associates and the Eastern Information Center, Archaeological Research Unit, University of California at Riverside.

Gray, Cliffton H., Jr.

1957 Tin. In: Mineral Commodities of California. State of California Department of Natural Resources, Division of Mines. Bulletin 176: 641-646.

Hoover, Mildred Brooke, Hero Eugene Rensch, and Ethel Grace Rensch

1966 Riverside County. In: Historic Spots in California. Revised and expanded by William N. Abeloe. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Tadlock, Jean, and Lewis Tadlock

1977 Archaeological Element of an Environmental Impact Report, Leighton Project No. 77023-1 (Tallichet-Hurford Ranch). Unpublished report on file at the Eastern Information Center, University of California at Riverside, MF No. 252.

The Perris Printing Company

1891 The Great Perris Valley, Southern California: Its History, Resources, Development. Holiday Supplement to the New Era, January 1, 1891. Perris Printing Company, Perris, California.